How the Internet Works

This image was generated in Photoshop Beta by the Adobe Firefly engine.

Most troubleshooting you will do as a systems librarian boils down to understanding how the internet works, and identifying where problems originate so you can contact the appropriate people for a resolution.

When an undergraduate has difficulty accessing a research database from off campus, is it an issue with their browser settings, their Single-Sign On account, the library’s proxy service, or the database vendor? When a faculty member reports that a record in the catalog is “broken,” is it a problem with the data in the ILS, a JavaScript or CSS customization, an indexing issue by the catalog host, or something else?

Though these scenarios can seem complex, the process of identifying the causes is straightforward: understand which systems are supposed to talk to each other at each step of the process, and look for breakdowns in the exchange of information. Either the library’s proxy service is receiving the expected response from the school’s Single Sign-On system, or it’s not. Either the catalog host’s servers are returning the correct data for a full record display, or they’re not.

This lesson will cover the basics of how this information exchange takes place, so you can work out which piece has gone awry in a variety of situations. These foundational concepts are particularly dense, so the contents will presented live over two sessions.

Recordings and Materials

Part I

Part I Slides (Presented September 12, 2024)

Part II

Part II Slides (Presented October 10, 2024)

In This lesson

- Servers and Clients

- IP Addresses

- Domain Name System (DNS)

- Requests and APIs

- Browser Tools

- Programming Languages

Servers and Clients

The modern World Wide Web took shape in the late 1980s at CERN (Conseil européen pour la Recherche nucléaire, or the European Organization for Nuclear Research). Computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee proposed linking the many siloed networks of international organizations together to create “a ‘web’ of notes with links (like references) between them” through Hypertext.

From Berners-Lee’s “Information Management: A Proposal,” 1989:

In 1980, I wrote a program for keeping track of software with which I was involved in the PS control system. Called Enquire, it allowed one to store snippets of information, and to link related pieces together in any way. To find information, one progressed via the links from one sheet to another, rather like in the old computer game “adventure”… Enquire, although lacking the fancy graphics, ran on a multiuser system, and allowed many people to access the same data.

Everything we do on the internet is an exchange of data between “clients” and “servers.” These terms have the same essential meaning as in colloquial English: when you visit a restaurant as a client, you place an order with your server, and they deliver the food you requested.

Similarly, when you visit a website, your browser is the client requesting the page from the server, and the physical or virtual machine hosting the website is the server that returns the page as HTML (Hypertext Markup Language). Servers can also return data in other formats for programmatic use, which will be covered under Requests and APIs below.

A “server” can also refer to one program on a machine. MySQL is a common database program that uses client/server architecture. If you want to install a WordPress website, you first need to install and configure the MySQL database server package, and then start the service. While the service is running, you can use the command-line client to tell the service to create databases, query them, update them, delete them, and so on. The future lesson Intro to Databases will expand on MySQL.

HTML, CSS, and JavaScript

You might have heard of many different languages, frameworks, and applications used to serve up websites, but they all generate documents with only three essential components for interpretation by a browser: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

HTML is the document type browsers display as a webpage. An HTML document consists of elements, also known as nodes, with a start tag (e.g., <div>), some contents like text and other child elements, and an end tag (e.g., </div>). Structurally, every document consists of a head, with invisible metadata like the title and references to styles and scripts; and a body, with the page contents rendered for users.

(Did You Know: the EPUB format for eBooks is just a compressed folder of HTML documents!)

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Page Title in the Browser Tab</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Big Header</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph.</p>

<p>

<a href="https://orbiscascade.org">

This is a link to the Orbis Cascade Alliance website.

</a>

</p>

</body>

</html>

CSS (Cascading Stylesheets) tells browsers how to render the appearance of webpages. CSS rules define aspects like colors, font sizes, the positioning of elements and the spacing between them.

In the head of HTML documents, CSS can be declared within a <style> element or a linked file that contains rulesets to apply to all elements that meet certain selection criteria (element name, class, ID, etc.). The style attribute can also be added to individual elements in the HTML body to override global rules.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Page Title in the Browser Tab</title>

<style>

body {

font-family: Times, serif;

}

p {

font-family: Arial, sans-serif;

}

a {

color: #007c89;

}

div.box {

border: 2px solid #00f;

background: #eee;

padding: 1rem;

margin: 0 0 1rem 0;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Big Header</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph in Arial font.</p>

<p>

<a href="https://orbiscascade.org">

This is a link to the Orbis Cascade Alliance website, in teal.

</a>

</p>

<div class="box">

This element will have a bright blue border

and a gray background.

</div>

<div class="box" style="background: #ffe; border-color: #f0f;">

The inline style attribute of this element will change

the background to yellow and the border to hot pink.

</div>

</body>

</html>

JavaScript manipulates HTML documents. For example, scripts can add and remove HTML elements, alter their contents and styling, trigger changes to the page when users click, scroll, or type, etc. JavaScript can appear anywhere in an HTML document, with functions in a <script> tag or a reference to a separate file.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Page Title in the Browser Tab</title>

<style>

#myBox {

border: 2px solid #00f;

background: #eee;

padding: 1rem;

}

#myBox span {

font-weight: bold;

}

</style>

<script>

function change_colors() {

var box = document.getElementById("myBox");

box.style.background = "#ffe";

box.style.borderColor = "#f0f";

document.getElementById("color1").textContent = "yellow";

document.getElementById("color2").textContent = "hot pink";

document.getElementById("myBtn").remove();

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Big Header</h1>

<div id="myBox">

This element will have a <span id="color1">gray</span>

background and a <span id="color2">bright blue</span>

border around it.

</div>

<p>

<button id="myBtn" onclick="change_colors();">

Click to change box colors and remove this button

</button>

</p>

</body>

</html>

There are many JavaScript libraries and frameworks that developers commonly choose for their sites, instead of writing code from scratch. Libraries are sets of functions that can be used to build or enhance any interface, while frameworks have standardized structures for deploying applications quickly. jQuery UI is a popular library that can be included on any webpage to add widgets and animations without extensive coding.

Most JavaScript frameworks are used for front end development, to manipulate HTML on the client. One example is Angular, which is used in Ex Libris’s Alma and Primo NDE products. Some JavaScript frameworks can also be used for back end development, to construct web servers. An example is Node.js, which is used in the Primo Development Environment.

To learn more about HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, these W3schools tutorials are a good starting point.

IP Addresses

Computers contact each other by IP Address. IP stands for Internet Protocol, the specification for constructing and assigning these identifiers.

IPv4, or Internet Protcol version 4, was deployed in the early 1980s. You’ll see IPv4 addresses written most often in “dot-decimal notation” with 4 numbers separated by periods. Each of these 4 numbers represents 8 bits, for a total of 32 bits.

Example: 35.82.168.182

Decimal: 35 82 168 182

Binary: 00100011|01010010|10101000|10110110

In IPv4, some address ranges are reserved for private use and others for public use.

Computers within a local network, like a home or a university campus, use private IP addresses to communicate with each other. These addresses begin with 10, 172.16 through 172.31, or 192.168. If a vendor asks for your IP address to whitelist a service, numbers in these ranges won’t be useful to them. The machine at 192.168.1.1 on their network will be different from the machine with the same address on your home or organization’s network.

To communicate over the internet, your ISP assigns your computer a public IP address, which is globally unique. You can check your public IP address simply by Googling “what is my IP address.” There are ways to change the IP address that servers receive and respond to, including proxies and VPNs. These topics will be covered in the next lesson, Security Basics.

IPv6, Internet Protocol version 6, became the latest standard in 2017. The number of possible unique 32-bit IPv4 addresses, about 4.29 billion, is too small to support the worldwide explosion of internet-connected devices for long. To solve this problem, IPv6 uses a 128-bit space, for approximately 340 undecillion possible unique addresses. (That’s 38 zeroes!)

IPv6 addresses are visually distinct from IPv4. Instead of 4 octets separated by periods, IPv6 addresses are written as eight 16-bit hexadecimal values separated by colons. Hexademical is a Base 16 numerical system that notates integers using both the numbers 0-9 and the letters A-F, in place of the double-digit decimals 10-15.

(Did You Know: Hexadecimal is also used for colors in CSS, as shown in the section above, with 3 values 00 through FF indicating the intensities of red, green, and blue.)

Example: 2600:1f14:1aa9:8f00:6368:4f33:28c5:1f50

Hexadecimal: 2600 1f14 1aa9 8f00 6368 4f33 28c5 1f50

Decimal: 9728 7956 6825 36608 25448 20275 10437 8016

Binary: 0010011000000000|0001111100010100|0001101010101001|1000111100000000|0110001101101000|0100111100110011|0010100011000101|0001111101010000

Notations with fewer than eight values indicate subnets within a network. For example, the subnet on AWS for the Orbis Cascade Alliance is 2600:1f14:1aa9:8f00::/64, which represents 256 possible IPv6 addresses. If your institution’s network supports IPv6, vendors with IP-restricted platforms might ask you to provide the subnet(s) for your campus(es).

Not all ISPs support IPv6 yet. According to Google’s IPv6 Statistics page, only about 45% of their users access services over IPv6 as of August 2024. If an ISP doesn’t support IPv6, their customers can’t use those addresses to contact servers. Because of this, websites need to support both protocols simultaneously for the foreseeable future.

Domain Name System (DNS)

Remembering long IP addresses for every website would be a nightmare, so in the 1980s the Domain Name System (DNS) was developed. DNS is like an old-fashioned phone book. Phone books listed the names of people and businesses in town with the numbers where they could be reached. Similarly, DNS associates human-friendly hostnames with the IP addresses of their servers, so users can type wikipedia.org into their browsers instead of 198.35.26.96.

On Windows, you can check a domain’s IP address(es) in the Command Prompt application with nslookup. You can find this application by searching Windows for “command” or “cmd,” or under the Control Panel > System and Security > Windows Tools. (The path will be different in versions before Windows 11.)

The command nslookup orbiscascade.org will return the result below, showing the IPv6 and IPv4 addresses of the server for the Orbis Cascade Alliance website on AWS.

Name: orbiscascade.org

Addresses: 2600:1f14:1aa9:8f00:6368:4f33:28c5:1f50

35.82.168.182

Before DNS, maps of hostnames and their IP addresses were recorded in HOSTS.TXT files. Hosts files can still be found on PCs and used to define domains that don’t yet exist on the internet, so they’ll work on that machine only. On Windows, this file lives at C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc\hosts. For example, if you need to test a new hosted service for the library and know the IP address from the vendor, you can add the domain you intend to use to this file. Then you can visit the domain in any browser on that computer.

# Copyright (c) 1993-2009 Microsoft Corp.

#

# This is a sample HOSTS file used by Microsoft TCP/IP for Windows.

#

# This file contains the mappings of IP addresses to host names. Each

# entry should be kept on an individual line. The IP address should

# be placed in the first column followed by the corresponding host name.

# The IP address and the host name should be separated by at least one

# space.

#

# Additionally, comments (such as these) may be inserted on individual

# lines or following the machine name denoted by a '#' symbol.

#

# For example:

#

# 102.54.94.97 rhino.acme.com # source server

# 38.25.63.10 x.acme.com # x client host

Taking this approach, you’ll likely encounter browser warnings about potential security risks. You might also see these warnings if you attempted to visit a website in a browser by its IP address instead of its domain. This is because neither a made-up domain nor the raw IP address matches a valid security certificate on the server. The next lesson, Security Basics, will address certificates and HTTPS.

DNS Zones and Records

Your organization’s IT department likely maintains the DNS zone(s) for your organization’s domain(s). These files live on nameservers that are defined when the organization purchases the domain from a registrar. Zone files contain several types of records to direct traffic to the appropriate servers.

A and AAAA records associate a domain with its IPv4 and IPv6 addresses, respectively. The orbiscascade.org zone contains A and AAAA records for the main website, plus subdomains like archiveswest.orbiscascade.org.

@ IN A 35.82.168.182

@ IN AAAA 2600:1f14:1aa9:8f00:6368:4f33:28c5:1f50

archiveswest IN A 35.86.54.0

archiveswest IN AAAA 2600:1f14:1aa9:8f00:c596:7c87:b1:cd0e

CNAME records associate a domain with another domain, rather than an IP address. When setting up hosted services to use your institution’s domain name, such as a librarysearch.myschool.edu for a discovery interface or research.myschool.edu for LibGuides, vendors will commonly instruct you to ask your IT department to set up a CNAME record.

For example, GitHub Pages hosts this course website, but visitors use github.orbiscascade.org to access it. A CNAME record in the orbiscascade.org zone forwards requests for github.orbiscascade.org to orbis-cascade-alliance.github.io. You could replace the URL in this browser with https://orbis-cascade-alliance.github.io/systems-librarianship/, and this site will load just the same.

github IN CNAME orbis-cascade-alliance.github.io.

Other record types are used for email routing and authentication, website ownership verification, and more niche applications. Some will be shown in the next lesson, Security Basics.

Requests and APIs

When using a web browser like Firefox or Chrome, the program sends HTTP requests and parses the responses for every link you click and search you submit. Many requests could fly back and forth to render one page, but they all have the same four components:

- An endpoint

- A method

- Headers

- A message body

The endpoint is the URL address of the resource the client needs.

The method is one of a limited set of actions a client may take through an HTTP request. These are the most common methods you’ll encounter as a systems librarian:

- GET retrieves information from the server. These requests may include some data in query parameters appended to the endpoint URL after a question mark (?), like https://www.google.com/search?q=test.

- POST sends information to the server, such as the filled fields of a web form. POST requests include data for the server in the message body, instead of the URL.

- PUT replaces data on the server with new content.

- DELETE removes a resource at the specified URL.

The headers pass metadata to the server. The fields could be which program is placing the request, required authorization credentials, the expected format of the response, and others.

The body contains the data for the server to act on. The body will be blank for most simple GET requests on your web browser, but it will contain objects for other types of requests.

In Windows, you can send HTTP requests to servers and see the raw responses in Command Prompt with curl. This command will add the required components for a well-structured message automatically, so at a minimum you only need to provide the endpoint. On execution, you’ll see what has been returned in the body of the response.

Try it with the simple HTML example in the first section of this lesson. The response will be the complete contents of the document, starting with <html>.

curl https://github.orbiscascade.org/systems-librarianship/_pages/includes/lesson1-example1.html

By default curl will use the GET method, or the POST method if you add some data to send to the server with the -d option. Try this one and see what you get back!

curl https://en.wikipedia.org/w/api.php -d "action=opensearch&search=orbis+cascade"

The example above is a call to an API (Application Programming Interface) that searches Wikipedia for article titles containing “orbis cascade” and returns an object with the submitted keywords, matching article titles, and URLs. You can experiment with changing the string after “search=” from “orbis+cascade” to different keywords like your favorite author or your own institution’s name. More examples and accepted parameters beyond “search” are listed in the MediaWiki Action API Documentation.

In general, APIs allow two applications to communicate. Many technology vendors offer APIs for institutions to interact with resources.

- Google APIs allow developers to interact with Google products. You could use these to fetch cover images from Google Books, programmatically add new rows to a Google Sheet, check for messages in a Gmail account, and so on.

- OCLC APIs allow queries of WorldCat and related data, like entities and FAST headings. These APIs could be used for performing collection analyses, adding linked data features to Discovery interfaces, etc.

- The Ex Libris APIs allow access to data in Clarivate products like Alma and Primo. Potential uses in library applications include checking open hours for display on a website, making corrections to bibliographic records en masse, performing Primo keyword searches for a Bento Box interface, or getting the results of a shared Analytics report.

- Springshare LibGuides offers an API to fetch links to existing guides, to display on LMS course pages for example.

For more experimentation, the Public APIs GitHub Repository lists known free APIs with a wide spectrum of uses, from generating random cat facts to querying photos taken by NASA’s rovers on Mars.

Responses and Status Codes

After a client submits an HTTP request, the server responds with a status code to indicate success or failure, along with headers and body similar to the structure of the request.

There are 599 potential status codes, but these are the ones you’re likely to encounter during troubleshooting and development:

- 200 OK: The request succeeded. The message body will contain the results, such as the webpage HTML or the expected output of an API call.

- 301 Moved Permanently: The requested resource is no longer at this URL. The body will contain the new one.

- 302 Found and 307 Temporary Redirect: The requested resource has been moved to a new location temporarily, but the same URL should be used for future requests.

- 403 Forbidden: The client doesn’t have permission to access this resource.

- 404 Not Found: The server can’t find a resource at the specified location.

- 500 Internal Server Error: The server doesn’t know how to handle this request. There could be a configuration problem on the server, or there could be something wrong with the structure or contents of the request.

- 503 Service Unavailable: The server can’t properly complete the request, for example because the application is down for maintenance.

Synchronization

Imagine you’re at a conference for librarians, and the catering staff wheels out the buffet table for lunch. On the table is a line of dishes with one serving spoon each. If dozens of attendees were to rush the table at once to get food, most of them couldn’t reach it in the chaos. Only a few people at the front could grab plates and serve themselves, while everyone else goes hungry.

Because we know this, consciously or not, the attendees will “synchronize” their movements. They’ll queue up at one end of the table, and each will wait patiently until the person before them has finished serving from a dish before stepping forward to take the spoon. This way we ensure everybody gets fed before the caterers cover the dishes and whisk the table away.

In computing, multiple processes could require access to limited resources. Similar to the conference buffet, a synchronous application will ensure the processes don’t try to execute all at once. The resources will be locked until one process is complete, and then the next process takes its turn. The application will return its results after all processes have finished.

Now imagine the conference doesn’t cater dinner, and you decide to order room service. You don’t know or care how many other hotel guests also want their dinners. You don’t have to coordinate with them. The kitchen will figure that out. You simply use the hotel’s phone line or website to place your order, and then you wait for staff to knock at your door with the food on a tray. In the meantime, you could watch television, take a well-deserved nap, or do any number of things.

Room service is like an asynchronous request in an application. Modern websites utilize asynchronous requests to return some information to users quickly, while loading more information that takes time to generate. The user can see and take other actions on the webpage, instead of waiting for the application to complete all tasks before returning everything at once. People often refer to these as AJAX requests (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML), which is the technique specific to web browsers.

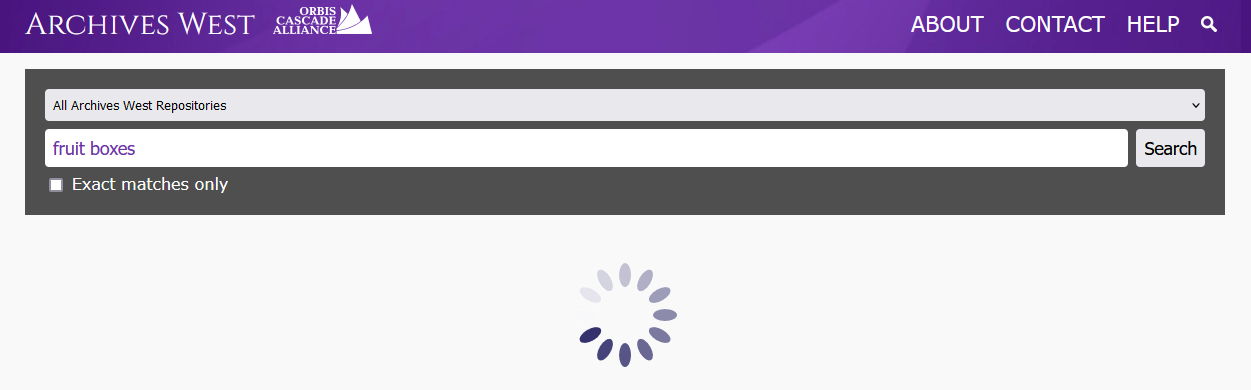

For example, if you submit any search in Archives West, you’ll first see a page with a spinning icon. This is the HTML content returned to the browser by the initial GET request.

As soon as the page loads, JavaScript submits an asynchronous request for the full-text search results, which will replace the spinning icon when the browser receives them.

The ubiquity of asynchronous requests in modern web applications means that in some situations, in addition to investigating whether information is being exchanged, you might need to consider when the information is supposed to be exchanged.

For example, Ex Libris’s Primo loads the many components of its interface through multiple asynchronous requests. Primo will perform separate individual requests for search results, availability statuses and call numbers, cover images, requesting options, and so on. When developing catalog customizations, it’s important to check whether the data you want to use exists at the time your code tries to use it.

Another example: many subscription databases load external scripts after the initial delivery of a page. If your institution uses EZproxy to provide off-campus access, these domains need to be added to your configuration with a special directive (HJ or DJ). Otherwise, only the original page contents will be proxied, and features dependent on these scripts won’t work properly. Proxying will be discussed more in Security Basics.

Browser Tools

Modern browsers include tools that allow you to examine the HTML structure, the loaded stylesheets and scripts, and all the requests and responses that take place to populate the webpage you see.

- In Mozilla Firefox, these are called the Web Developer Tools.

- In Google Chrome, Developer Tools

- In Microsoft Edge, DevTools

All three can be opened on Windows with the F12 key, or the shortcut CTRL+SHIFT+I. You can try it on this very page.

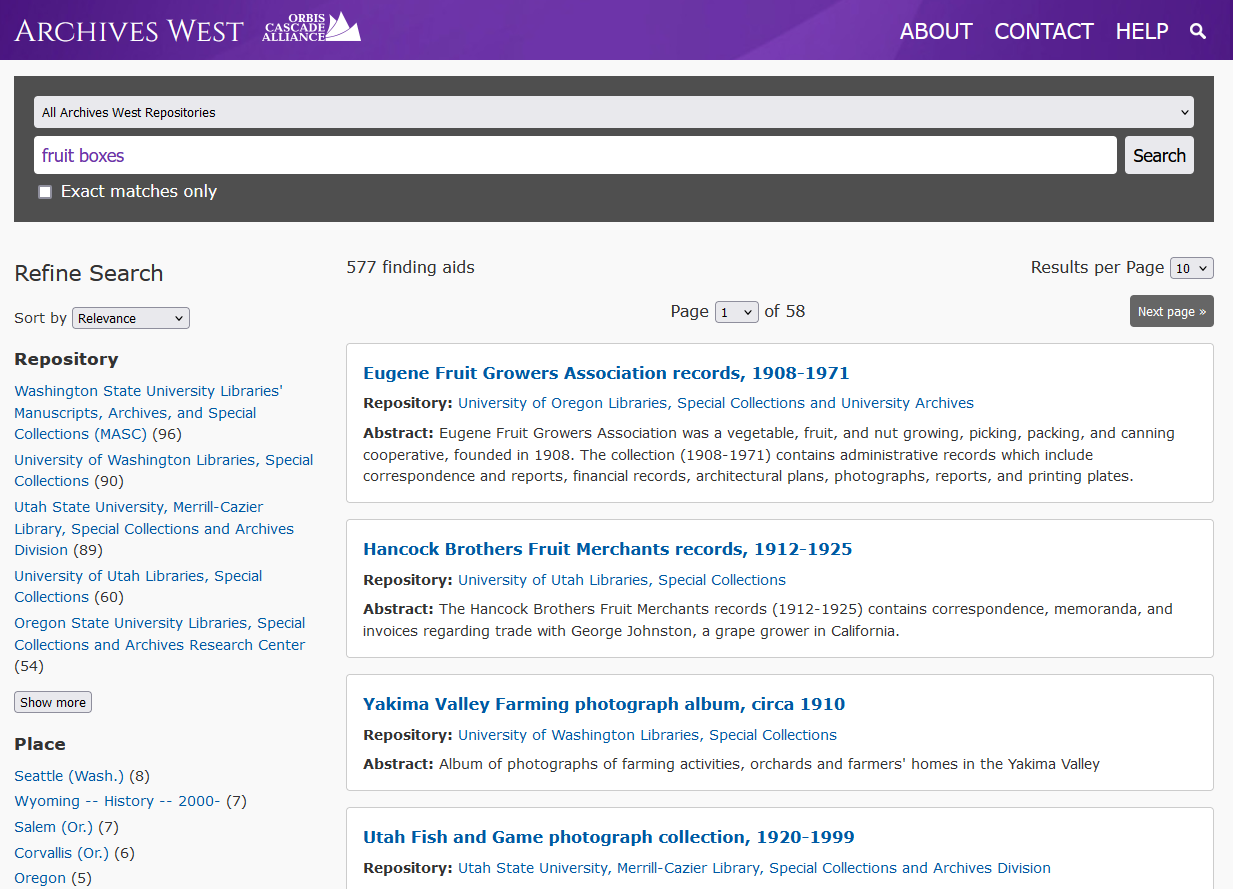

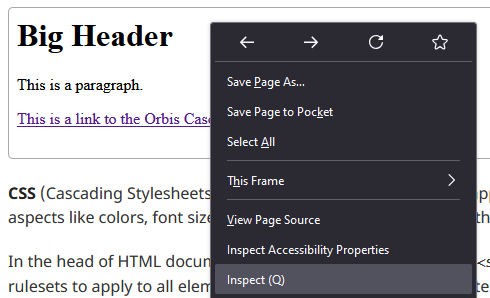

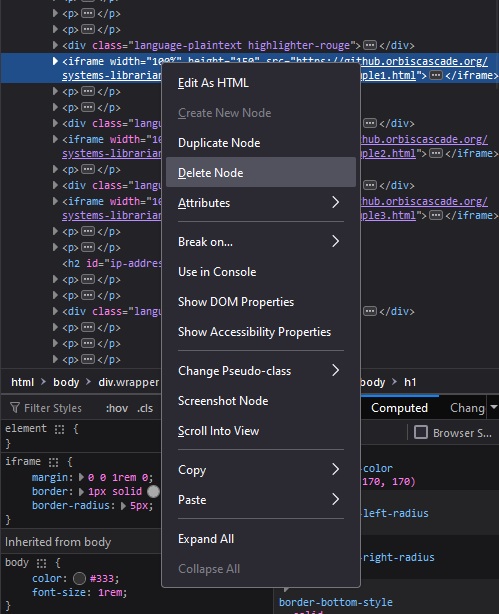

No matter which browser you’re in, one tab of these tools will allow you to see the HTML. It might be called Inspector or Elements. Try opening various HTML elements and matching them to what you see on the screen. To examine the HTML of a particular element on the page, you can right-click it and select “Inspect.”

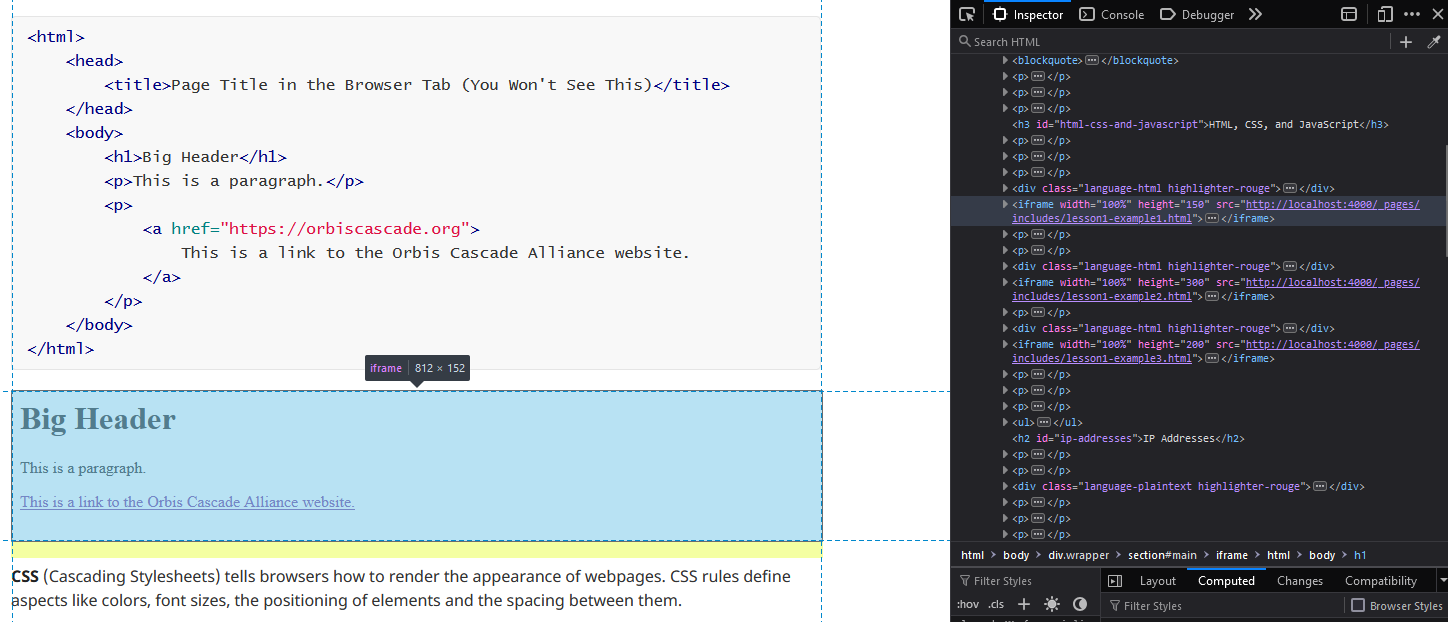

The screenshot below of Firefox’s tools highlights the iframe element used to display the simple HTML sample in the first section. (You can click the image to view a larger version.)

If you want, you can manipulate the HTML to change how the page looks. Try right-clicking on an HTML element and selecting Delete Node or Delete Element. That content will disappear from the webpage. You can also rewrite the contents of elements with “Edit As HTML”. It’s okay, you’re only making these changes on the client, not the server. All elements will reappear in their original states after you refresh the page.

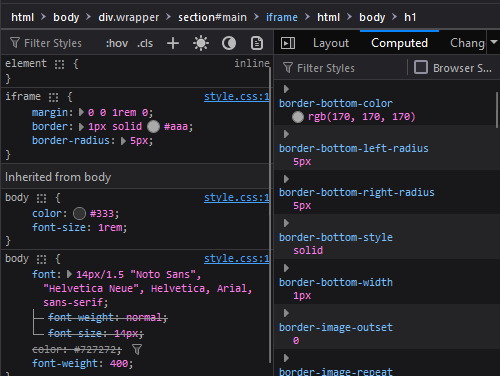

The Inspector/Elements tab will also show you the CSS applied to the element you’re examining, including the rules as written and the results as computed.

You can adjust the CSS rules here to see what happens. This is a great way to test stylesheet changes to a web interface without making them permanent or public. Here I’ve added “background: green” to iframes for illustrative purposes.

When troubleshooting potential JavaScript issues, you’ll often find helpful clues in the Console tab, which is available in all three major browsers. The console will display messages printed by functions, as well as warnings and errors.

Try opening the console in your browser’s tools right now, and then click the button below to see a message appear there. Bonus challenge: can you find the JavaScript function that does this?

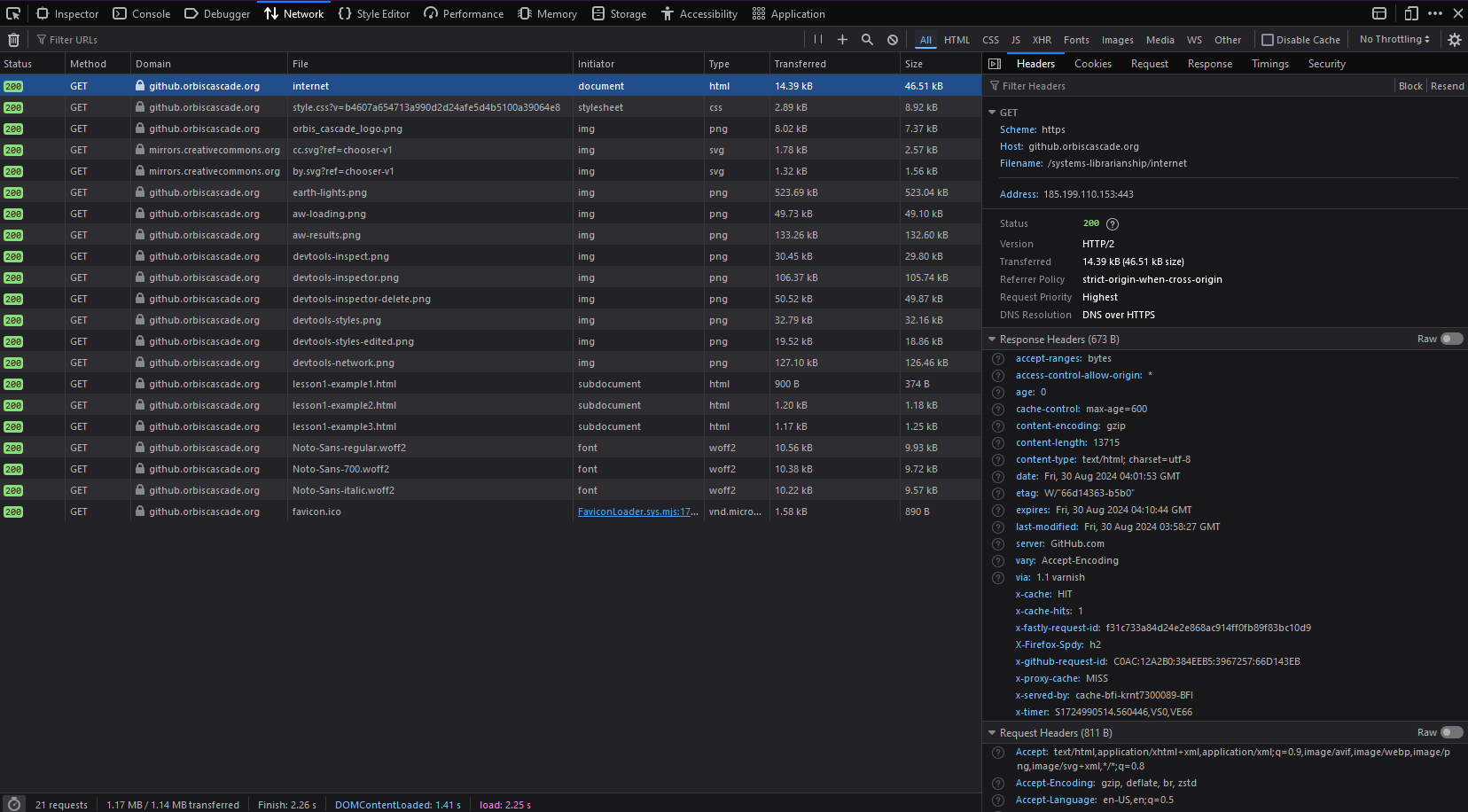

Network is another tab you’ll use frequently as a systems librarian. While this tab is open, you can see every request the browser places, and the status codes and contents of the responses. They’ll include the initial HTML of a webpage, plus all images, subdocuments (such as the HTML examples in iframes), and asynchronous requests triggered by a user action or a timer. Click one of the requests in the list to see all the headers and message bodies described in the Requests and APIs section.

Each browser has additional tabs you might find useful, like for seeing and manipulating stored cookies and checking for accessibility issues. Try them all to see what information you can get.

Programming Languages

A common question new systems librarians ask is, “Which programming language should I learn?” The maddening answer they’ll receive is, “It depends on what you want to do.” But also, to be blunt, it doesn’t matter much.

A dizzying number of programming languages exist, and they can be categorized in different ways: compiled or interpreted; procedural, functional, or object-oriented; server-side or client-side. The distinctions are important in computer science. As a budding programmer for libraries, though, your experience using any one of them will be more or less the same as the others.

- You’ll install required packages for that language on a machine.

- You’ll write human-readable source code following the syntax of that language.

- Your source code will be converted into executable code computers can run.

This is true of JavaScript as well, though you might not have thought you installed anything special. The web browsers themselves contain the interpreters that run JavaScript code. That’s why it’s important to test webpages with custom scripts on all major browsers: a script that works as intended in Firefox could break in Chrome, or vice versa.

Below are some programming languages you’re likely to encounter in library applications, in alphabetical order. Over time, you might experiment with all of these languages and more. You’ll begin to see more similarities than differences between them. No matter which you try first, you’ll learn basic concepts in programming like using variables, conditions and operators, loops, etc. that you’ll later find in nearly every language.

-

Java is widely used for desktop applications, like the Windows version of SpineOMatic. Users must have Java installed on their personal computers to run these programs. Java is also used for Android app development. You won’t likely need to develop a Java application as a systems librarian, but you might need to run some.

-

PHP (PHP Hypertext Preprocessing) is a popular scripting language for web development. The open-source CMSs WordPress and Drupal are written in PHP, as is the Orbis Cascade Alliance’s Archives West. If you intend to develop websites for your library, PHP is a good choice to learn.

-

Python is commonly used for personal projects that automate tasks or analyze large amounts of data. Because Python was designed to be a simple language to read and write, and there are many libraries that can do complex tasks for you (like creating GUIs and performing mathematical computations), you can create programs that do a lot with little coding. Though Python can be used to construct web servers, it’s best suited for running scripts on your own machine.

-

Ruby is the language used for open-source library platforms like Blacklight and ArchivesSpace. This course website is generated with Jekyll, which is also a Ruby framework.

-

Visual Basic is a Windows-specific language created by Microsoft. You’re most likely to encounter it as VBA (Visual Basic for Applications), used for writing macros in Microsoft 365 programs. One example is the Excel Alma Lookup plugin by Princeton University Library.

-

XSLT (Extensible Stylesheet Language Transformations) does only one thing: convert data from XML into another type of document, usually HTML. XSLT is common in library work, such as when customizing letters in Ex Libris Alma or working with descriptive finding aids in EAD. Web browsers can display XML documents directly as webpages, given an XSLT stylesheet. However, the transformation is inefficient, and you’re unlikely to encounter modern websites that do this.