Introduction to Databases

This image was generated in Photoshop Beta by the Adobe Firefly engine.

As systems librarians, nearly everything we work with uses databases: our catalogs, Student Information Sytems, websites, digital collections platforms, etc. However, people don’t often discuss exactly what databases are or how they work. When I typed the prompt to generate the image at the top of this page, “Illustration of a computer monitor displaying a database,” even an AI model trained on vast amounts of visual data had no idea what I meant! The program generated pictures of monitors showing bar and line graphs, world maps, or the generic database icon of stacked cylinders, which is what I landed on because every other attempt I made at description failed.

This lesson will provide a short overview of the types of databases most relevant to library work, how they structure data for storage and querying, and how they use indexes for speedy information retrieval in real-world applications.

Recordings and Materials

Slides (for presentation December 12, 2024)

In This lesson

Database Types

Hierarchical

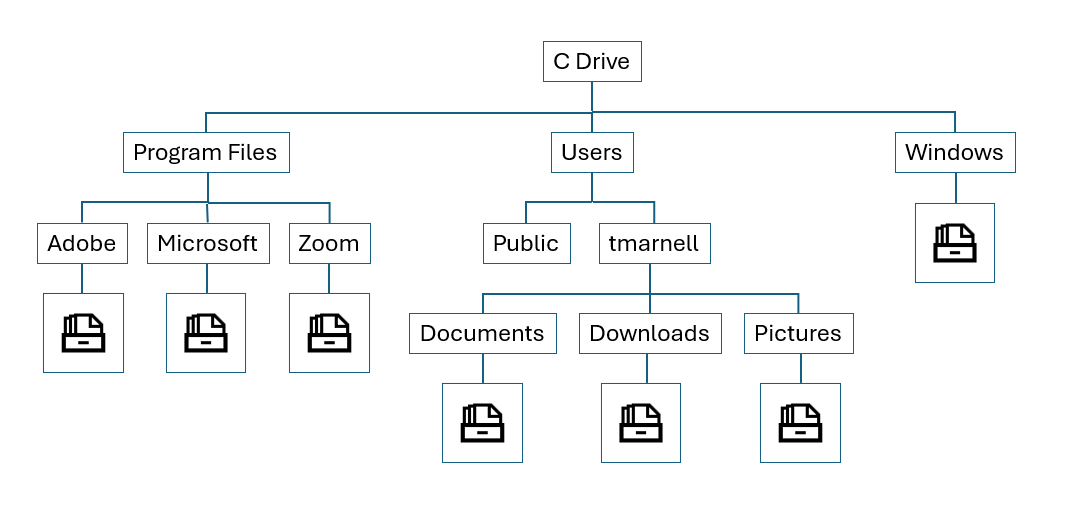

The oldest and least flexible type, hierarchical databases are trees of parents and children. This kind of system can only accommodate a one-to-many relationship: a parent record can have multiple children, but a child record can have only one parent. For a script to find a particular record, it needs to transverse the entire tree from the “root.”

The Windows, Linux, and older Apple filing systems are hierarchical. In Windows, the root of each hierarchy is a volume, often represented by a letter like “C.” Within C: you’ll find directories like Program Files, Users, and Windows. Within Program Files, there’s a directory for each publisher or package, and so on. Searching the C: drive for a particular known document takes a long time, because the Windows Explorer program needs to dig down through every “branch” to find it.

Relational

To overcome the limitations of the hierarchical data structure, in the 1970s employees at IBM defined and developed a new model for storage: relational databases.

This is the type of database most often taught in library school classes and professional workshops. Popular applications for relational databases include Microsoft Access and MySQL, which both use Structured Query Language (SQL) to store, manipulate, and retrieve data.

Relational databases store data in tables, with categories of data like text strings, integers, dates, limited sets, etc. in columns, and individual records in rows. Unique values in the rows can be used to join tables together in any imaginable combination. This allows relational databases to support many-to-many relationships: records in one table can be related to any number of records in another table, and vice versa.

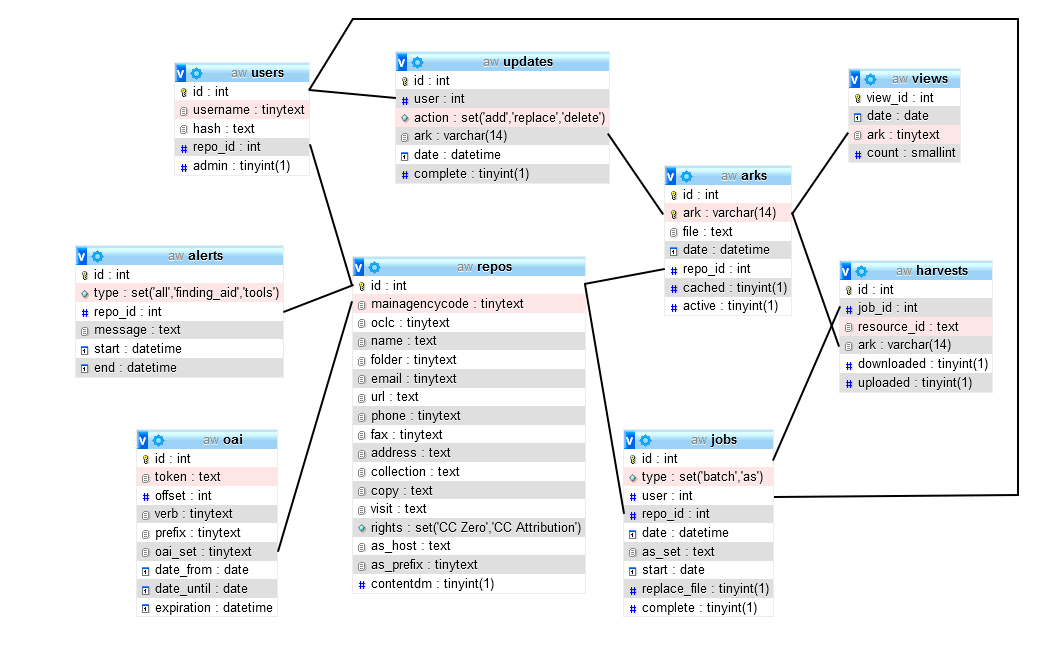

The diagram below represents the tables in the MySQL database of Archives West.

Note that none of the pictured relationships are many-to-many. Developers working with relational databases prefer to use bridge tables to avoid duplicating data. These break up a many-to-many relationship into two one-to-many relationships. For example, each import job in Archives West could affect many ARKs, and each ARK could also be affected by many jobs, but ARKs aren’t stored in the jobs table or vice versa. Instead, the “harvests” table stores records that each have only one job ID and one ARK. Jobs can be associated with many harvest processes, and ARKs can also be associated with many harvest processes, but independently each of these relationships is one-to-many.

Now let’s look at how we can use these relationships between tables to extract the data we want. Let’s say we want to look up information about the repository that owns a certain finding aid with the ARK “80444/xv605573.” The “repos” table contains a unique identifier for every participating repository. The “arks” table stores the same identifier as the column “repo_id.” Therefore, we can look up the name and URL of the repository this ARK belongs to with an SQL statement like this:

SELECT repos.name, repos.url

-> FROM repos JOIN arks ON repos.id=arks.repo_id

-> WHERE arks.ark="80444/xv605573";

+--------------------------------------------+-------------------------------------+

| name | url |

+--------------------------------------------+-------------------------------------+

| Oregon Historical Society Research Library | http://ohs.org/research-and-library |

+--------------------------------------------+-------------------------------------+

Data from tables without a direct link between them can be queried with multiple joins. For example, this statement would return the total views of finding aids belonging to the University of Washington in October 2024, though no repository information is in the “views” table.

SELECT repos.name, COUNT(DISTINCT views.ark) as arks, SUM(views.count) as total

-> FROM (repos JOIN arks ON repos.id=arks.repo_id)

-> JOIN views ON arks.ark=views.ark

-> WHERE repos.name LIKE "University of Washington %"

-> AND views.date BETWEEN "2024-10-01" AND "2024-10-31"

-> GROUP BY repos.name;

+---------------------------------------------------------+------+-------+

| name | arks | total |

+---------------------------------------------------------+------+-------+

| University of Washington Ethnomusicology Archives | 1062 | 1723 |

| University of Washington Libraries, Media Archive | 4 | 14 |

| University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections | 2848 | 14204 |

+---------------------------------------------------------+------+-------+

More complex queries can be constructed to return aggregations and calculations, queries based on the results of other subqueries, pivot tables (e.g., the number of finding aid views per fiscal quarter), etc. To learn more, the Carpentries organization offers an excellent openly licensed course on SQL here: Library Carpentry: SQL.

Beyond its common use in databases for custom applications, SQL can also be used to create reports in Integrated Library Systems like Koha, III Polaris, and SirsiDynix Symphony, and to customize queries and filters in platforms like Oracle Business Insights. This Ex Libris Tech Blog post offers many examples: Alma Analytics - SQL Filter Examples.

Non-Relational

Not all kinds of data can be efficiently stored in tables of columns and rows. Many types of library and archival records, for example, were originally envisioned as XML documents with dozens of optional fields for description. A MySQL database consisting of a single table with 999 columns for all possible MARC fields would be painfully slow to update and query, and it wouldn’t take advantage of any of the benefits of the relational model described above.

In the twenty-first century, non-relational or NoSQL database models grew in popularity for these cases. Though many subtypes of non-relational databases exist, two are particularly relevant to library work: key-value stores and document databases.

Key-value stores are what the name implies: a simple database of unique keys associated with some values. The values are “opaque,” meaning the system doesn’t know anything about what they are or how they’re structured, it only stores and delivers them. They could be JSON objects, XML documents, images and videos, or a mix of different things. While these databases don’t support complex queries like SQL, they can respond to requests very quickly. Amazon Web Services DynamoDB is a popular platform for building key-value databases.

Document databases are like key-value stores, but with structured documents instead of any possible value. These documents are “transparent,” meaning the system knows what they contain and can manipulate and query them. This is ideal for library applications that make long, irregular descriptive records searchable.

-

Apache Solr is the document database utilized by open-source Discovery projects like Blacklight, Aspen, and ArchivesSpace. To harvest records into Solr, developers create “schema” to define which fields the documents contain. When a new document is added to the database, Solr finds these fields and adds them to a searchable index (more on indexes below).

-

BaseX is the XML-specific document database utilized by Archives West to index Encoded Archival Description (EAD) finding aids. While some essential data required to run Archives West benefits from storage in MySQL, as illustrated above, a document database is more appropriate for making EADs full-text searchable. Once XML documents are added to a BaseX database, users can fetch their contents with the functional programming language XQuery. See BaseX for Newbies for more in-depth explanations and examples.

-

MongoDB is another popular program for creating databases of JSON-like documents. The community edition can be self-hosted for free, however the cloud and enterprise editions are licensed products with fees.

Indexes

In your library work, you’ve probably heard talk of indexing in various systems. Your catalog vendor might say a set of records needs to be “reindexed” for searches to return the expected results. Or a MySQL workshop instructor might have mentioned that you can create indexes based on table columns to speed up your queries.

What is an index? Like many other technical terms in this course so far–like client, server, password, etc.–“index” was simply plucked from colloquial English. Long before the age of computers, print materials like textbooks contained back-of-the-book indexes: alphabetical lists of subject headings with associated page numbers.

For example, Acquisitions: Core Concepts and Practices (2017) by Jesse Holden has an index that begins like this:

academic libraries, 42–44, 67, 109

access

alternate strategies of, 101–103

definition of, 8–9

establishing, as core competency, 7, 10, 24–25, 43–44, 103, 112–113

ownership and, 44–46

potential for, 76–77

strategic assemblages of, 43–51

vendors and, 28–37

acquisitions

archives and, 103–106

as an assemblage, 7, 12–13, 50–51, 57–58, 80, 99–103, 110–116

changing nature of, 21–24, 75–81, 103, 114–116

core competencies in, 7, 10, 24–25, 103, 112–113

definition of, 6–9

linearity and, 24, 26–27, 29, 48, 54–55, 113–115

professional standards for, 14–15, 29–30, 34–37, 77, 95

radicalization of, 15–17, 110–116

rhizomatic approach to, 115–116

role of, 15–17, 24–27, 49–51, 54–58, 72–75, 95–97, 104–105

If someone wants to read about acquisitions and archives, they can look at this index to see where the topic is covered, then flip directly to pages 103-106. They don’t have to skim through all 102 pages before that to find it.

A database index is the same: a condensed reference an application can use to quickly deliver requested information, instead of combing slowly and painfully through large amounts of data.

The document databases of Archives West contain over forty thousand EAD finding aids, some of which would be hundreds or thousands of pages long if printed. Without indexes, searching all of those EADs for submitted keywords could take over a minute. Going through the original file of each resulting finding aid to get its abstract would take even more time, as would collecting all the related controlled vocabulary terms to display in facets on the side.

No user in the 2020s has the patience for that! Instead, the application builds indexes from the contents of submitted EADs.

-

A full text index that stores tokenized words or phrases and pointers to the documents they appear in

-

A brief result index that contains only the titles, abstracts, and upload dates associated with each document identifier (ARK)

-

Multiple facet indexes, which are custom document databases of subjects, persons, geographical locations, etc. and the ARKs of the documents that contain them

Here’s an example of a facet index for subjects in one of the repositories of Archives West.

<terms db="18">

<term text="Advertising and Marketing">

<ark>80444/xv44537</ark>

<ark>80444/xv33883</ark>

</term>

<term text="Agriculture">

<ark>80444/xv32205</ark>

</term>

<term text="Arab Americans">

<ark>80444/xv87927</ark>

</term>

<term text="Artifacts">

<ark>80444/xv76818</ark>

</term>

<term text="Astoria">

<ark>80444/xv83142</ark>

</term>

(...)

</terms>

Each of the participating repositories in Archives West has a similar document database. With this structure, the application can quickly check fortyish short documents for finding aids that contain the subject term “Artifacts,” instead of reading through forty thousand long documents! In reverse, scripts can use the index to fetch all of the subjects associated with the ARKs in a set of full-text results, so users can further refine their queries.

Most research platforms likely take a similar approach to the different components of their interfaces, and they query indexes rather than source records in MARC, Dublin Core, EAD, etc. Though you might not need to build a website like Archives West from scratch, understanding where applications rely on indexes will come in handy for some common troubleshooting scenarios.

Examples:

-

Catalogers created new bibliographic records, but they’re not appearing in test searches of your Discovery layer. This is likely because the job to index catalog records for searching hasn’t run yet or has failed.

-

Your library changed the name of a location, but the old name is still appearing in the facets/filters section of your Discovery layer. This is likely because all records with holdings in the renamed location need to be reindexed.

-

Your colleagues expect known records with a certain local field to come up in a keyword search, but they don’t. That field might not be included in the searchable index(es) of your Discovery layer, and some configuration and/or normalization rules are required.